Electron rest mass

| Values of me | Units |

|---|---|

| 9.109 382 15(45)×10−31 | kg |

| 5.485 799 0943(23)×10−4 | u |

| 8.187 104 38(41)×10−14 | J/c2 |

| 0.510 998 910(13) | MeV/c2 |

| Values of the energy of me | Units |

| 8.187 104 38(41)×10−14 | J |

| 0.510 998 910(13) | MeV |

The electron rest mass (symbol: me) is the mass of a stationary electron. It is one of the fundamental constants of physics, and is also very important in chemistry because of its relation to the Avogadro constant. It has a value of about 9.11×10−31 kilograms or about 5.486×10−4 atomic mass units, equivalent to an energy of about 8.19×10−14 joules or about 0.511 megaelectronvolts.[1]

Contents |

Terminology

The term "rest mass" comes from the need to take account of the effects of special relativity on the apparent (or "observed") mass of an electron. It is impossible to "weigh" a stationary electron, and so all practical measurements must be carried out on moving electrons. However special relativity shows that the mass of an object appears to increase as its speed v (relative to the observer) approaches the speed of light c. The 2006 CODATA recommended value for the electron rest mass (in atomic units) has a measurement uncertainty of 4.2×10−10: this is equivalent to relativistic correction to the observed mass of a body travelling at 3×10−5c, or about 9000 m/s. Although this is a high speed in normal experience, it is very low in terms of subatomic particles: for an electron, it corresponds to a kinetic energy of 2.15×10−4 eV, or the energy gained by an electron when it is accelerated through a potential difference of just 0.215 mV.

Electron relative atomic mass

In metrology, the electron rest mass can refer to two separate and independent quantities. The first is the rest mass of an electron in SI units (or any other macroscopic system of units). The second is the rest mass of the electron on the scale used to measure relative atomic masses, where the mass of an atom of carbon 12 has a value of exactly 12. CODATA refers to this second quantity as the electron relative atomic mass, with the symbol Ar(e),[1] regardless that the electron is not an atom. The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) refers to the quantity as the electron mass in u (atomic mass units),[2] but this term involves a circular definition as discussed below.

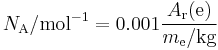

The distinction is important because the two quantities are determined by completely different methods, so the "electron mass in u" is not calculated from the electron mass in kilograms, or vice versa. The ratio of the two quantities, multiplied by a constant factor, gives the Avogadro constant NA:

The factor of 0.001 is the molar mass constant, Mu, which is defined as 0.001 kg/mol in SI units.[1]

Determination

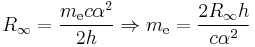

The electron rest mass in kilograms is calculated from the definition of the Rydberg constant R∞:

where α is the fine structure constant and h is the Planck constant.[1] The relative uncertainty, 5×10−8 in the 2006 CODATA recommended value,[2] is due entirely to the uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant.

The electron relative atomic mass can be measured directly in a Penning trap. It can also be inferred from the spectra of antiprotonic helium atoms (helium atoms where one of the electrons has been replaced by an antiproton) or from measurements of the electron g-factor in the hydrogenic ions 12C5+ or 16O7+. The 2006 CODATA recommended value has a relative uncertainty of 4.2×10−10.[1]

The electron relative atomic mass is an adjusted parameter in the CODATA set of fundamental physical constants, while the electron rest mass in kilograms is calculated from the values of the Planck constant, the fine structure constant and the Rydberg constant.[1] The correlation between the two values is negligible (r = 0.0003).[2]

Relationship to other physical constants

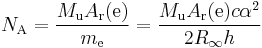

As mentioned above, the electron mass is used to calculate the Avogadro constant NA:

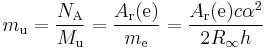

Hence it is also related to the atomic mass constant mu:

Note that mu is defined in terms of Ar(e), and not the other way round, and so the name "electron mass in atomic mass units" for Ar(e) involves a circular definition (at least in terms of practical measurements).

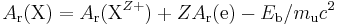

The electron relative atomic mass also enters into the calculation of all other relative atomic masses. By convention, relative atomic masses are quoted for neutral atoms, but the actual measurements are made on positive ions, either in a mass spectrometer or a Penning trap. Hence the mass of the electrons must be added back on to the measured values before tabulation. A correction must also be made for the mass equivalent of the binding energy Eb. Taking the simplest case of complete ionization of all electrons, for a nuclide X of atomic number Z,[1]

As relative atomic masses are measured as ratios of masses, the corrections must be applied to both ions: fortunately, the uncertainties in the corrections are negligible, as illustrated below for hydrogen 1 and oxygen 16.

| 1H | 16O | |

|---|---|---|

| relative atomic mass of the XZ+ ion | 1.007 276 466 77(10) | 15.990 528 174 45(18) |

| relative atomic mass of the Z electrons | 0.000 548 579 909 43(23) | 0.004 388 639 2754(18) |

| correction for the binding energy | −0.000 000 014 5985 | −0.000 002 194 1559 |

| relative atomic mass of the neutral atom | 1.007 825 032 07(10) | 15.994 914 619 57(18) |

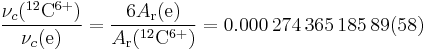

The principle can be shown by the determination of the electron relative atomic mass by Farnham et al. at the University of Washington (1995).[3] It involves the measurement of the frequencies of the cyclotron radiation emitted by electrons and by 12C6+ ions in a Penning trap. The ratio of the two frequencies is equal to six times the inverse ratio of the masses of the two particles (the heavier the particle, the lower the frequency of the cyclotron radiation; the higher the charge on the particle, the higher the frequency):

As the relative atomic mass of 12C6+ ions is very nearly 12, the ratio of frequencies can be used to calculate a first approximation to Ar(e), 5.487 303 7178×10−4. This approximate value is then used to calculate a first approximation to Ar(12C6+), knowing that Eb(12C)/muc2 (from the sum of the six ionization energies of carbon) is 1.105 8674×10−6: Ar(12C6+) ≈ 11.996 708 723 6367. This value is then used to calculate a new approximation to Ar(e), and the process repeated until the values no longer vary (given the relative uncertainty of the measurement, 2.1×10−9): this happens by the fourth cycle of iterations for these results, giving Ar(e) = 5.485 799 111(12)×10−4 for these data.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Mohr, Peter J.; Taylor, Barry N.; Newell, David B. (2008). "CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006". Rev. Mod. Phys. 80: 633–730. Bibcode 2008RvMP...80..633M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.633. http://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/codata.pdf.

- ^ a b c The NIST reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty, National Institute of Standards and Technology, http://physics.nist.gov/cuu/index.html

- ^ Farnham, D. L.; Van Dyck, Jr., R. S.; Schwinberg, P. B. (1995), "Determination of the Electron's Atomic Mass and the Proton/Electron Mass Ratio via Penning Trap Mass Spectroscopy", Phys. Rev. Lett. 75 (20): 3598–3601, Bibcode 1995PhRvL..75.3598F, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.3598